How to Survive Graduate School: ADHD Edition

Author: Tegan Hargreaves

I was diagnosed with the combined type of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) at the age of 28, after completing almost 8 years of postsecondary education (4 years undergraduate, 2 years masters, and almost 2 years of a PhD). Women are often diagnosed with ADHD later in life; when we are finally diagnosed, it’s common to struggle to pick up the pieces of the identity you used to know and mourn the “I could’ve beens”. When I was diagnosed, all the coping mechanisms and survival tactics I had acquired over my almost 30 years of life seemed to dwindle away, leaving a shell of a person trying to finish a doctorate, while also trying to figure out who I actually am.

Do I have it all figured out? Absolutely not. My days are still filled with “I wish”; I wish I had more publications, a larger network, more productivity on a day-to-day basis, and that I didn’t feel like I constantly have to make apologies and reparations for the person I want to be but still cannot find. Executive dysfunction finds me at every turn, leadings to days and weeks where the most I can accomplish is opening my Word document with my manuscript.

But I do know that I am much better off than when I started my PhD. I have more insight into myself and what I need to feel fulfilled. I’ve learned how to work with my ADHD and neurodivergence, trying to focus on the things that I can and do add to the field of addictions neuroscience as someone with ADHD. My endless curiosity and unrelenting search for “what else” can be a hinderance at times but also drives my love of the scientific process. It’s also helped me learn a wide variety of skills. My enthusiasm allows for mentorship opportunities where those I have mentored actually feel like they’ve learned something. My ability to hyperfocus has served me well under pressure, along with my ability to work incredibly well under significant time constraints.

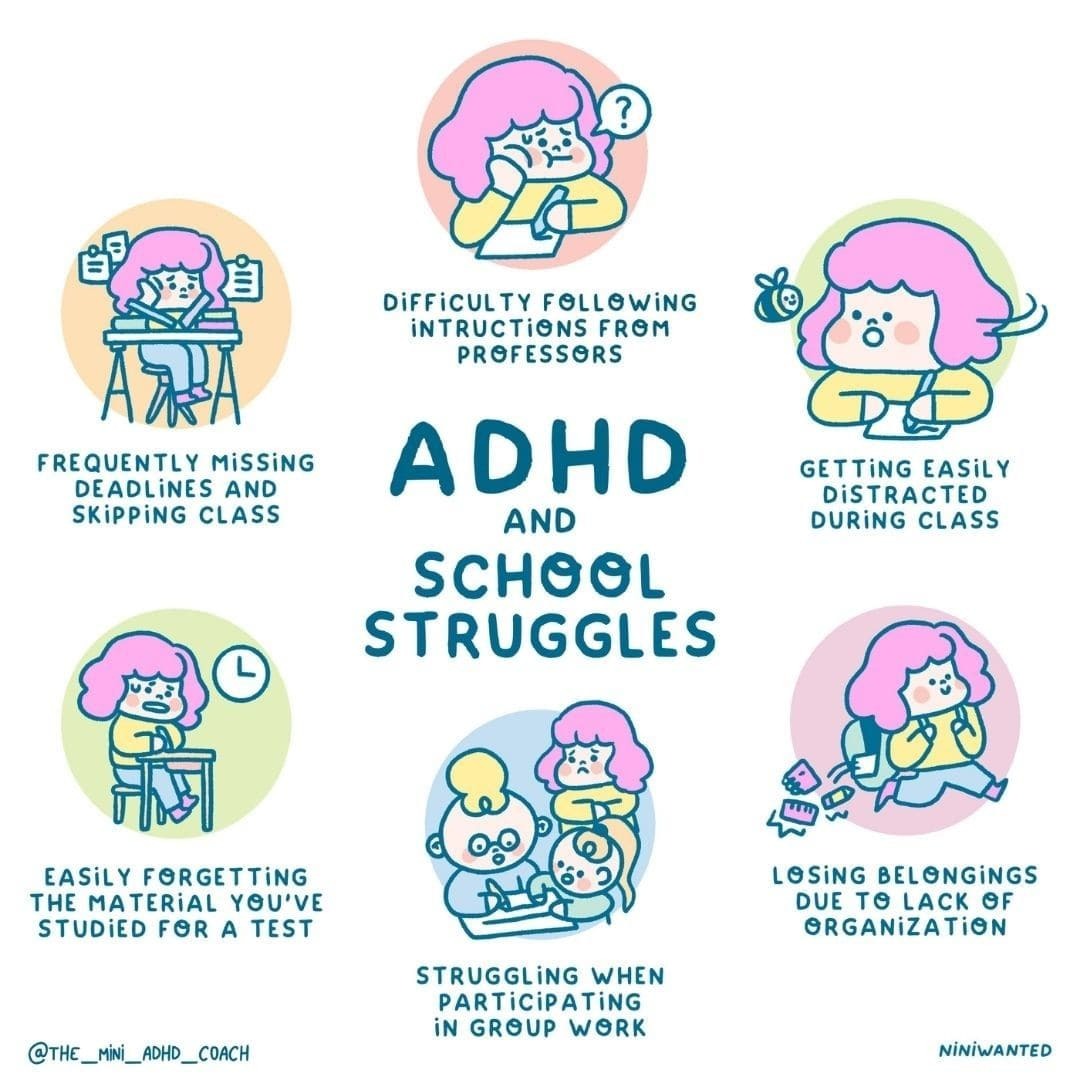

All of this is to say that graduate school is a long and taxing journey; surviving graduate school with ADHD can feel impossible. Often, when you look for advice on managing ADHD, it’s not geared to graduate students or scientists, it’s geared to the general public or undergraduate students. I am passionate about offering my knowledge and experience to those who could benefit; therefore, here is a list of things I have found to actually be useful in managing my ADHD, while continuing to make progress in my PhD.

3. Body doubling: Without realizing what it was called, I had been using body doubling for years to get things done, both related to school and general things in my life. Body doubling is “a productivity strategy used by individuals with ADHD to finish possibly annoying jobs while having another person beside them. This person is the body double. The body double’s duty is to keep the individual with ADHD focused on the task at hand to reduce potential distractions and increase motivation.” (source). I’ve found it to be an incredibly powerful tool in getting things accomplished and you’ll often find me setting up virtual work dates to boost my productivity, knowing I need to be physically at my desk.

4. Loop earplugs: Like most neurodivergent individuals, I am extremely sensitive to sound. I hyperfocus on repetitive noises and loud noises are too loud; then I become irritable and can shut down. I recently bought a pair of Loop earplugs and they have made such a huge difference. I also have noise cancelling headphones if I want to listen to music, but the ability to throw in some discrete earplugs is a game-changer for me.

5. Setting the stage for productivity: Something my therapist recently recommended was creating a space that enhances productivity, accompanied by specific cues that would help promote “work mode”. Knowing the importance of the senses in building neural connections, I’ve been working to create an environment that is specifically geared towards being productive. I have a “work candle” and a “work blanket”, and I have turned my office into exclusively a work zone (i.e., I take actual breaks outside of my office, I don’t go into my office unless I’m working).

7. Timers: Every person with ADHD or any ADHD resource will comment on the importance of timers. Personally, I struggle a lot with time blindness. I often have no clue how long something will take me to execute, leading to inability to start the task due to overwhelm or the finished product is incredibly delayed because I massively underestimated the amount of time it would take to finish. I have found that timing frequently repeated events (e.g., how long will it take me to analyze one participant’s data?) keeps me realistic in my timelines and prevents me from getting too frazzled or behind.

8. Support network: My support network is invaluable to me. My spouse, friends, family, labmates, and of course, my dog, are what help push me through when things feel impossible. I feel very fortunate to have the support that I do; they are often the people who are lifting me up and cheering me on when I feel like I’m not doing or am not enough.

9. Resources: Student Accessibility Services is a fantastic resource to have. While I have seldom needed to use my accommodations, knowing they are available to me makes me feel less overwhelmed when I do need them.

10. Disclosing your ADHD: If your supervisor feels like a safe space and you feel comfortable disclosing, I can’t recommend this enough. Having my supervisor be knowledgeable about what I am dealing with and how my limitations may vary has helped make my graduate experience much better. I am incredibly fortunate that my supervisor has given me the grace and patience to navigate my neurodivergence in the ways that feel authentic to me. If you are considering disclosing and are unsure if it's a good idea, here is a great sheet from the Student Accessibility Services that discusses when to disclose.

11. Setting aside time for myself to avoid burnout: This has been something I’ve definitely learned the hard way this academic year. With ADHD, everything feels very “in the moment” and “right now”, which can be helpful in graduate school. However, when you continue to offer the finite resources and energy you have, eventually you hit the bottom of your pile of resources and are left totally burnt out. At the beginning of 2025, I hit a wall and felt like I crashed. I now better recognize the importance of setting aside time for myself every day, whether that be my newest hobby, taking the time to spend time with my friends, or going on a date with my husband. These are all things that have helped to refill my cup and allow me to continue to show up as my best self in the final months of the program.

Overall, I don’t have it all figured out, nor do I have a perfect system. Some days sitting at my desk and playing silly phone games is the best that I can do. On others, I can write the discussion section of a paper that I’ve been putting off for weeks. Despite this, I have still built a method to the madness that works enough, which lets me be a scientist, a student, and a silly goose.

Completing grad school with ADHD isn’t about catching up or normalizing to the mean (little stats joke there); it’s about refusing to shrink yourself down to what a scientist “should” look like and building the most authentic version of yourself (even if that version includes earplugs, a carefully curated calendar, half full mugs of cold coffee, and a “work mode” candle).

I’ve come to learn that there is so much power in learning who you are. There's softness in being kind to yourself and offering yourself grace, but there's a lot of strength in showing up as you are and reminding yourself that you belong here, chaos and all.