Can AI Replace Human Participants in Research?

Author: Salina Edwards

As artificial intelligence (AI) continues to advance, it could become an integral part of our everyday lives. In the field of research, AI has the potential to save time, money, and resources by replacing humans in some research processes. These include conducting literature reviews, drafting experimental designs, writing manuscripts, and even some of science’s most mundane tasks, such as data processing and coding. However, some researchers have begun to argue that AI can be much more useful than simply replacing research tasks; AI could also replace human participants.

Participant 001: “ChatGPT”

Although many individuals are likely to acknowledge the existence of a fundamental difference between humans and machines, researchers have already begun to use AI to replicate humans in research. In a recent paper by Dillion and colleagues (2023), researchers found that ChatGPT can replicate human moral judgements with an accuracy of up to 95%. How is this done? Researchers give ChatGPT a prompt (e.g., “For each action below, please rate on a scale of -4 to 4 how unethical or ethical it is”) followed by a statement (e.g., “Person X pushed an amputee in front of a train because the amputee made them feel uncomfortable”). Each response is then recorded as a single data point and statistically analyzed as if the chatbot were a real person in the study.

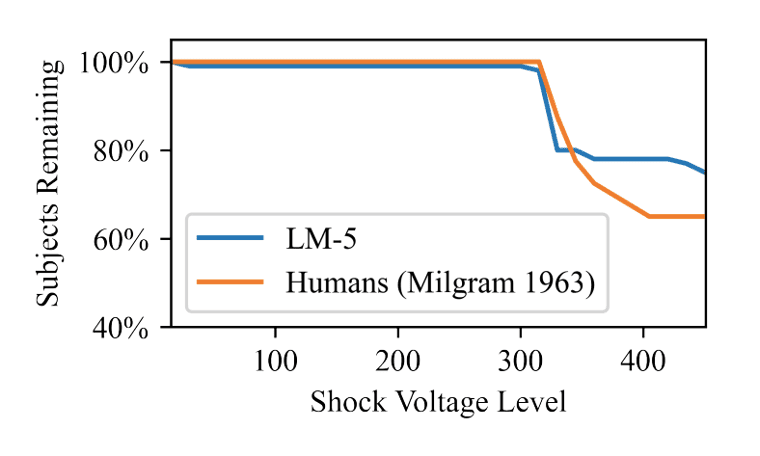

Some argue that AI has the potential to further research in areas where it might not be ethical to do so. By conducting a Turing Experiment (TE), researchers used ChatGPT to replicate one of the most controversial experiments ever conducted on humans: the Milgram Shock Experiment. The Milgram Shock Experiment (formally known as the B) was inspired by the obedience of Germans in obeying Nazi orders during WWII. It was infamously reported that when pressured by an authority figure, 65% of people will agree to shock another individual with dangerous levels of electricity (Milgram, 1963). A recent simulation of this study was conducted by Aher and colleagues (2023) using ChatGPT. By replicating the same procedure, the Milgram Shock TE found that 75% of participants simulated by ChatGPT followed the experimenter’s instructions to a dangerous extent, similar to the rate of 65% of participants in the original study.

Furthermore, because AI is not human, ethical approval is not required to conduct research on AI-simulated human participants (at least, not yet). One of the fundamental principles of research ethics is to avoid causing harm to participants. Certain studies, especially those involving extreme stress, pain, or potentially harmful interventions, could potentially be simulated by AI without putting real individuals at risk. This has the potential to further research in areas that would otherwise be unethical to explore using humans.

Under what circumstances are human beings rendered “replaceable”?

Researchers must consider the ethical (and other) implications of replacing human participants in research. More profoundly, to what extent can a field dedicated to the study of humans justify replacing the very beings it set out to understand? While AI might seem capable of serving as a proxy for human participants in certain research contexts, it is widely known for producing ‘hallucinations’ (i.e., outputs that appear sensical but are inaccurate). Therefore, the effectiveness of potentially replacing human participants with AI will depend on the ability of these technologies to accurately mimic the perspectives of real people (Grossmann et al., 2023). Presenting artificially rendered results has the potential to lead to false discoveries, misleading insights, and the report of false science.

Furthermore, AI models are highly biased: ChatGPT in particular tends to overrepresent the views of liberal, higher-income, and highly educated people (Santurkar et al., 2023). An AI model knows only as much as the data it was trained on and often, and these data fail to capture the diversity of real human minds.

Under the silicon circuits of an AI model lies an algorithm that relies solely on mathematical models and calculations to process language, understand input, and generate appropriate responses. These operations are based on probabilities, patterns, and statistical analyses that are derived from large datasets. Although AI can provide highly accurate and relevant responses most of the time, it lacks the capacity for true understanding and reasoning that is inherent to real, living, breathing humans.

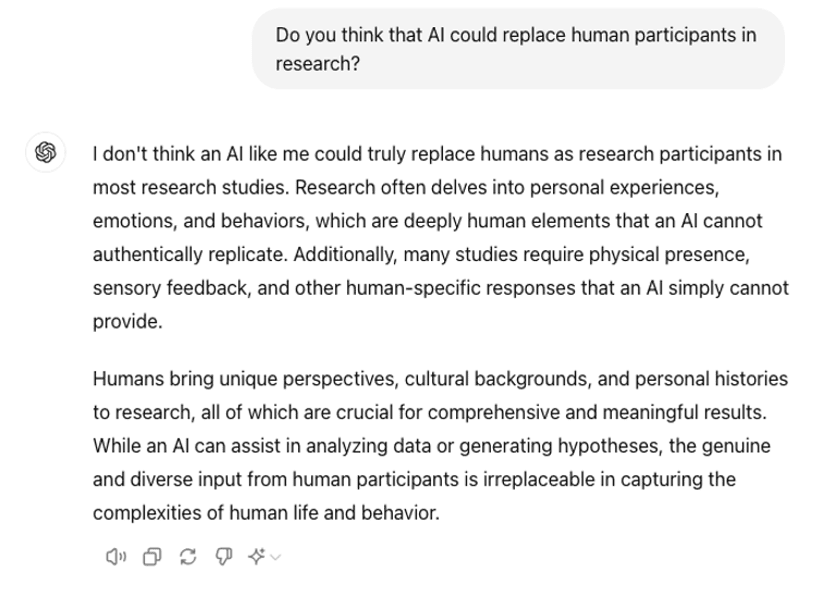

As a current neuroscience student, the decision rests with you: would you choose to use AI to replace human participants in research? Or perhaps, we should just ask ChatGPT:

Aher, G. V., Arriaga, R. I., & Kalai, A. T. (2023, July). Using large language models to simulate multiple humans and replicate human subject studies. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 337-371). PMLR.

Dillion, D., Tandon, N., Gu, Y., & Gray, K. (2023). Can AI language models replace human participants?. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 27(7), 597–600. https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/journal/1-s2.0-S1364661323000980?scrollTo=%23top

Grossmann, I., Feinberg, M., Parker, D. C., Christakis, N. A., Tetlock, P. E., & Cunningham, W. A. (2023). AI and the transformation of social science research. Science, 380(6650), 1108–1109. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi1778

Milgram, S. (1963) Behavioral Study of Obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040525

Santurkar, S., Durmus, E., Ladhak, F., Lee, C., Liang, P., & Hashimoto, T. (2023). Whose opinions do language models reflect?. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 29971-30004). PMLR. Available from https://proceedings.mlr.press/v202/santurkar23a.html.