Understanding Humans Using Non-Human Animals: A Brief History of Animal Models in Neuroscience

Author: Salina Edwards

“The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.”

Non-human animals have played a fundamental role in advancing the field of neuroscience since its inception. The earliest records documenting the use of non-human animals as models for human anatomy and physiology in research began in ancient Greece (Neziri et al., 2024; Ericsson et al., 2013).

Early comparative science was often observational, aiming to better understand human development and physiology. However, while human cadavers were commonly used for anatomical dissections--frequently drawing a rather large and curious audience--it was not uncommon for deceased animals to be used in their place when human corpses were unavailable.

Alcmaeon of Croton, an early Greek medical writer, philosopher-scientist, and student of Pythagoras, is often credited as being the first to observe non-human animals and draw comparisons to humans (Celesia, 2012; Ericsson et al., 2013). Using empirical observations, Alcmaeon concluded that the eye is connected to the skull via a channel or path, concluding that principatum esse in cerebro (the governing faculty is in the brain; Celesia, 2013). Alcmaeon is also credited as being the first to use dissection of animals for the purpose of studying anatomy (Singer, 1925).

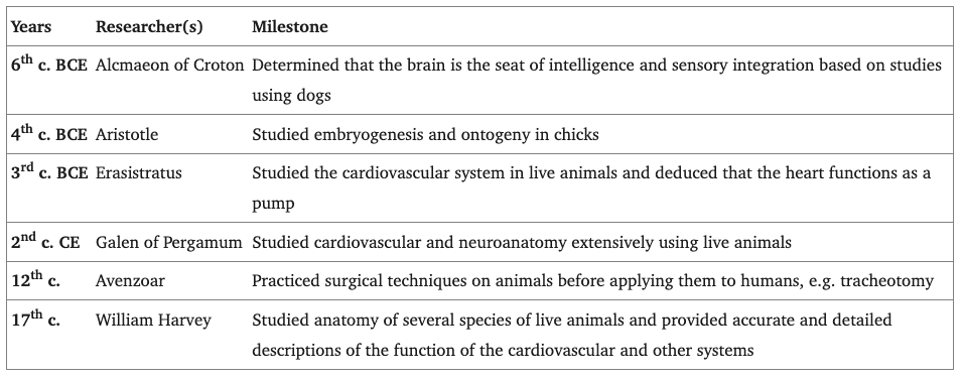

Table 1. Early Milestones in Animal Modeling. Adapted from Ericsson et al. (2013).

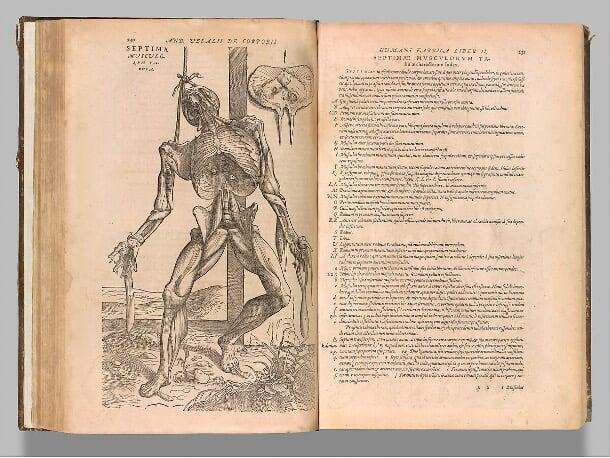

During the Renaissance, comparative science flourished. Flemish surgeon and anatomist Vesalius (1514-1564) explored the varying features between human and animal anatomies, often performing live slaughtering lessons on animals for students studying medicine (Yoladi et al., 2023). Vesalius revolutionized the study of anatomy with the publication of his magnum opus De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body). This work drew upon his own studies, correcting many of Galen’s errors in anatomy, and is considered one of the most influential books on the subject (Siraisi, 1997; see Fig. 2).

The use of animal models in research increased dramatically by the 20th century:

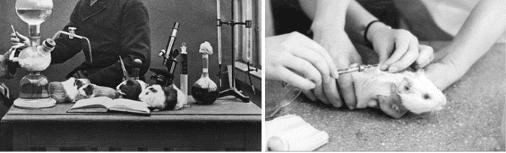

- In 1921, Otto Loewi stimulated frogs' hearts using electrical impulses, leaving them beating in an ionic bath. After transferring this same fluid to another heart, he observed it operating similarly. This experiment (which came to him in a dream*) led to the discovery of neurotransmitters. In 1936, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contributions (McCoy & Tan, 2014).

- In the 1920s, Edgar Adrian developed the theory of neural communication using an isolated frog nerve-muscle preparation. He showed that signal magnitude is conveyed through the frequency of action potentials rather than their size. Adrian was also awarded a Nobel Prize for his work (Enroth-Cugell, 1993).

- In the 1940s, John Cade explored the effects of lithium salts on guinea pigs while searching for anticonvulsant drugs (see Fig. 3). He observed that the animals appeared calmer, leading him to experiment with lithium on himself before using it to manage recurrent mania. By the 1970s, lithium had transformed the treatment of manic depression, which previously relied on lobotomies or electroconvulsive therapy (Parker, 2012).