What was graduate life like before the advent of digital technology? An interview with insights from Drs. Fahnestock, McCabe, and Minuzzi

Author: Salina Edwards

“When I was in graduate school, there was no such thing as ‘digital.’” – Dr. Margaret Fahnestock

Let’s face it: digital technology spoils us. Rather than spending hours sifting through the library to find that perfect quote, we can scroll through decades of literature at the click of a button. I will gladly take a little bit of extra blue-light exposure just to CTRL + F my way through a reading.

How did students navigate grad school before the digital age? I interviewed three Neuroscience faculty members from McMaster University to find out.

Meet Dr. Margaret Fahnestock: A molecular neuroscientist exploring the biosynthesis and regulation of neurotrophins. Dr. Fahnestock completed her PhD studying bacterial chemotaxis at the University of California Berkeley in from 1974-1979. She is a highly respected researcher in her field and has been a member of McMaster University since 1991. Even before the internet, a literature review never phased her.

“All literature reviews were performed in person by reading hard-copy journals subscribed to by the library,” she explained. “One could keep up with relevant progress by reading perhaps a dozen journals in one’s field! I spent many long hours reading in the library and I still have boxes of important papers that I photocopied in the library to keep in my files for reference. In 1985, I was able to send an e-mail to a colleague in Australia via DARPAnet, the US Army-supported precursor to the internet. Prior to that time, I would stay up until the wee hours of the morning so that I could call him on the phone during his working hours. In 1986, my department got its first computer, an Osborne ‘portable’ the size of a large suitcase that used 5-1/4” floppy discs and had 64kb of memory. There was no internet for almost another decade.”

Despite the major change from analogue to digital, Dr. Fahnestock says there is one thing that hasn’t changed: The ability to communicate orally and in writing. “The most valuable skill is critical thinking, and the second most valuable skill is the ability to communicate,” she said. “That hasn’t changed. Technology now enables grammar and spelling correction, but I find most students don’t use those, and they don’t help much with clarity of communication.”

In this regard, Dr. Fahnestock is absolutely correct! In fact, a recent study exploring the advantages of AI and learning found that students often tend to rely on AI for assistance, rather than learn from it (Darvishi et al., 2024).

So, what has changed? If Dr. Fahnestock could give advice to someone in graduate school in the past and present, she would say the same thing: “When I was in graduate school, I did not realize how important networking is. I would advise myself and students now to take advantage of all opportunities to meet people and to make sure people know them! That includes going to seminars and meeting speakers before and after, giving talks or posters whenever possible, talking to students and professors in other labs, and asking questions at webinars or seminars. Same advice then and now!”

When Dr. Randi McCabe was in school, “there was no internet. It was just starting at the time, so there was no email! Everything was submitted using regular mail.”

Dr. McCabe currently researches cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), factors related to phenomenology and treatment for anxiety disorders, and the development and refinement of assessment tools at McMaster University. She completed her PhD at the University of Toronto (UofT) in 2000, with a focus on cognitive biases related to dieting and eating disorders.

For her, life was different in many ways. For one, “grant applications were typed on a common typewriter in the graduate studies department,” explained Dr. McCabe. “Then you would photocopy it to have the required number of copies that they would submit to all the reviewers. It took ages to do this.”

Even today it feels like time is fleeting. Imagine making a single typo on your typewriter: There is no backspace that could sail save you.

For Dr. McCabe, a typical day in graduate school looked like this:

- “Going to class and hanging out in the basement of Sidney Smith Hall at UofT where the computers were located to run our statistical analyses using SAS,

- Spending hours at the library to look up journals and books to read and photocopy articles,

- Marking hundreds of papers as a teaching assistant,

- Running participants through research studies and hanging out in the lab where my lab mates made food like cookies and pizza for their studies (we studied eating and its disorders),

- Lots of writing, and

- Taking breaks for fun like going to the gym or going out with friends.”

“Grad school was fun, and I didn’t really appreciate the freedom I had at that time to decide what to study and the open periods of time to just think, read, discuss ideas, and write,” says Dr. McCabe. “I think it is true that when you are in something, it is hard to have the perspective to appreciate it. Once you get into your career, schedules get increasingly busy, and that freedom becomes exceedingly rare. Enjoy the process!”

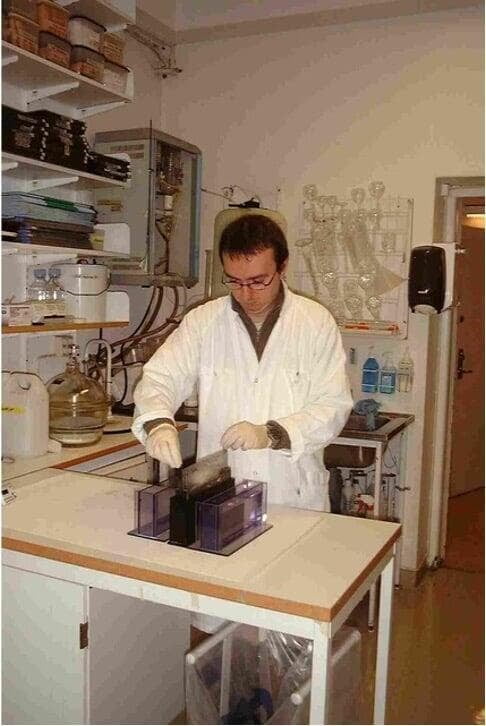

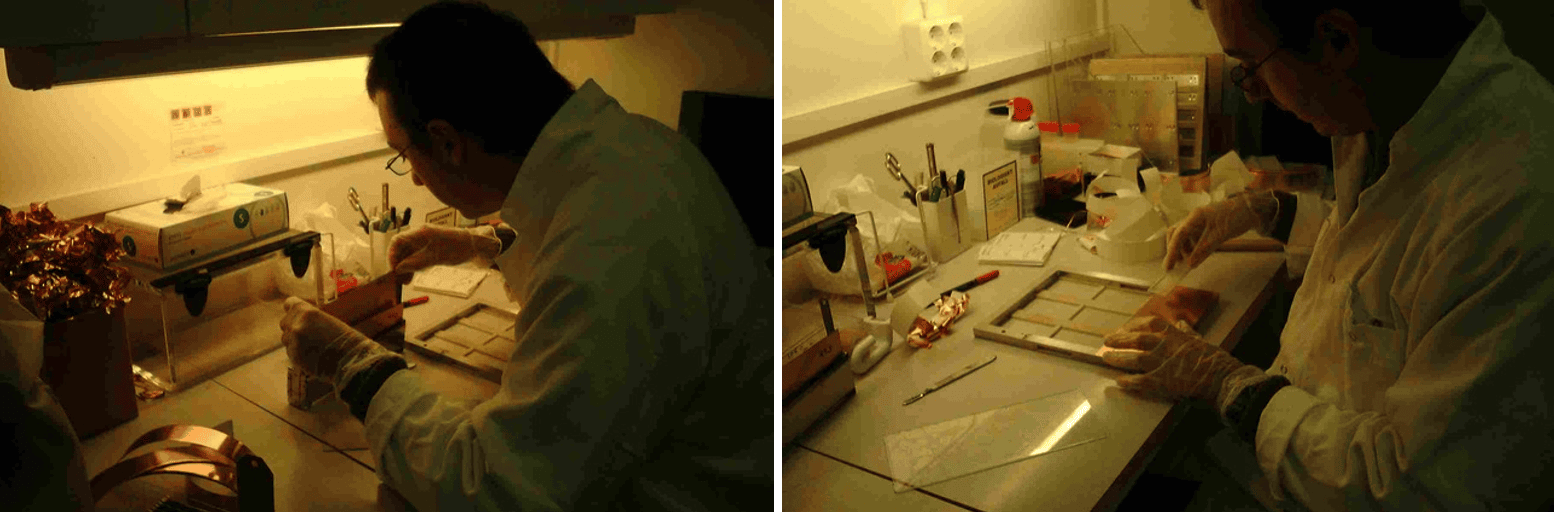

Dr. Luciano Minuzzi completed his PhD at Aarhus University in Demark quantifying monoamine receptors (dopamine, serotonin, histamine, and norepinephrine) in animal models of schizophrenia using in vitro (autoradiography) and in vivo (positron emission tomography) techniques. Today, Dr. Minuzzi’s research focuses on brain neurotransmission, the association between hormones and mental health disorders and markers for treatment and prevention.

For Dr. Minuzzi, the internet already existed during his PhD. “I am not that old!” he jokes. “Although, most journals were not fully available online”

As a graduate student living in Denmark, Dr. Minuzzi spent most of his time at the lab. “I shared an apartment with five other graduate students from different countries,” he said. “So, my morning routine involved chatting with my roommates while trying to prepare coffee in a small kitchen! Then I would go to the lab and spend all day there doing experiments, analyzing data, and writing. I also spent a good part of my day reading and learning. The lab was located in the hospital which had a gym for the employees and students, meaning that even to workout I didn’t need to go far away. I would go back home very late (around 11:00 pm or past midnight, depending on the experiments I was doing in the lab). It was an exciting time, and I learned a lot.”

While digital technology often facilitates daily tasks, Dr. Minuzzi provides an interesting perspective on how graduate work has changed: “I find it is more difficult now to keep up with new research compared to when I was in graduate school. I think the amount of information available now is significantly larger than before, and this growth may be explained by the increase in online publishing and the expansion of research institutions. Recently, I read that in the early 2020s, the number of scientific journals had more than doubled compared to the early 2000s!”

That is quite an advancement in just a mere 20 years! I can’t even imagine what academia might look like in the year 2045.

If there’s one piece of information Dr. Minuzzi would give to himself in grad school, he would say: “I would advise myself to find a better balance between work and personal life. You can still be very productive academically but also have a fulfilling life outside the university. That is also my advice for students now, especially with the amount of information available that can be overwhelming. My other advice for students now is to spend time focusing on mastering basic scientific skills, like data analysis, statistics, and scientific writing.”

Thank you to Drs. Fahnestock, McCabe, and Minuzzi for their wonderful insights! We appreciate you sitting down with Salina.

References

Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., Gašević, D., & Siemens, G. (2024). Impact of AI assistance on student agency. Computers & Education, 210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104967