Achieving Small Goals: Your Personalised Blueprint

Author: Anne-Marie Di Passa

Is there something you’ve been meaning to achieve, but you just can’t seem to get started?

When we think of goals, we often think big. Unrealistically BIG. When we think of our idealized goals, like becoming a sculpted bodybuilder or an astronaut, the chances of us achieving this goal remains slim if we consider the goal in its ultimate form. What I mean by this is: how likely am I to really make the necessary behavioural changes to become a sculpted bodybuilder by framing my goal as such? Very unlikely. Why? Because I am thinking in terms of A to Z, not A to B, B to C, or C to D, etc. Breaking down your goals into smaller and simpler steps, as well as rewarding yourself at each step, can be an effective method to pave the way of gradually achieving your future goals (Berkman, 2018). This lies in the premise of reinforcement learning which elucidates the challenges of making behavioural changes and rewiring the stubbornly wired reward centres of the brain.

Enough about wires— Is there something you’ve been wanting to improve on or learn lately? Perhaps developing a healthy behaviour, learning a new skill, taking better care of yourself, or being kinder to others? Together, right now, we are going to draft a blueprint for you to create a well-structured goal.

If you’re struggling to come up with a small goal, here are some ideas of you can choose from:

- Going to bed earlier by half hour increments

- Exercising for at least 20 minutes a day for 3 days per week

- Eating healthier (i.e., more hearty greens, more fibre)

- Meditating for 5 minutes per day (then gradually increasing)

- Practising gratitude (e.g., spending 5 minutes a day writing down what you’re grateful for)

- Learning a new language (e.g., completing one lesson on Duolingo per day)

- Bettering your relationships (e.g., calling or texting your grandparents/parents/friends at least once per day to check in on them)

- Giving out heartfelt compliments to at least one person per day

- Learning to be more assertive (i.e., practising saying “no”, letting other people know you’re not in a place to give advice or be vented at, using more “I feel” statements, etc.)

Let’s start from the beginning:

GRAB A SHEET OF PAPER AND A PEN! (Otherwise stop reading).

You are going to write:

[your name]’s [OPTIONAL FUN ADJECTIVE] goal

For example, “Anne-Marie’s AUDACIOUS Healthy Eating Goal”

Next write:

I want to [stop/start] (select one) _______ [behaviour/habit]______

Did you just write “stop” in the entry above? Erase or scratch out the word “stop.” We don’t need negativity. In fact, according to psychology, it’s all about the way you phrase it. Are you starting a new behaviour or simply resisting/eliminating an old one? The way you phrase your goal has an impact on its success. Approach goals involve incorporating a new behaviour, whereas avoidance goals aim to reduce or eliminate a behaviour. Approach goals are more likely to generate positive emotions and enhance well-being compared to avoidance goals, which can evoke negative emotions (Bailey, 2017). Though there may be many habits in our lives we want to get rid of, it might be a better suggestion to rephrase our avoidance goal. For example, I have a really bad habit of eating sweets. Sometimes when I’m bored, I will just eat chocolate and zone out. Although I would like to say, “I want to stop eating chocolate and sweets,” I can reframe this idea to something like: “Whenever I begin craving chocolate and/or sweets, I can start eating healthier dessert substitutes, such as chia-seed pudding, oat squares, or dark chocolate date bars.” Restructuring your goals with a positive mindset will help increase the likelihood of its success!

So, if you wrote “stop” above, rewrite your goal with “start.”

You should now have a sentence resembling, “I want to/can start ___ [behaviour/habit]___”Now, how can we make this goal better? Here are some strategies:

1. Be honest with yourself and your core values.

In terms of level of difficulty, how would you rate the difficulty of achieving this goal on a scale of 1 (piece of cake) to 10 (seems impossibly hard)? If it's anything below a 2, you may want to increase the difficulty to anywhere between 3 to 8— challenging, but not too easy or impossibly hard. Easy goals are often met with low effort, leading to low performance (Gauggel et al., 2002).

What is more important than a goal’s perceived difficulty? The intrinsic motivation behind it! Did you choose this goal because it aligns with your personal values and inner aspirations (i.e., intrinsic motivation)? Or did you choose it because you want to impress others, make money, or gain other external rewards (i.e., extrinsic motivation)? If you answered yes to the latter, you may want to choose a goal that intrinsically motivates you. For example, my goal to start eating healthier dessert substitutes is driven by my core values of health and self-confidence (intrinsic motivators), not by wanting to look better for other people (an extrinsic motivator). Intrinsic motivation has been shown to be more effective in promoting successful goal achievement, despite a goal’s difficulty. In fact, people are willing to work on a difficult goal if it intrinsically motivates them (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

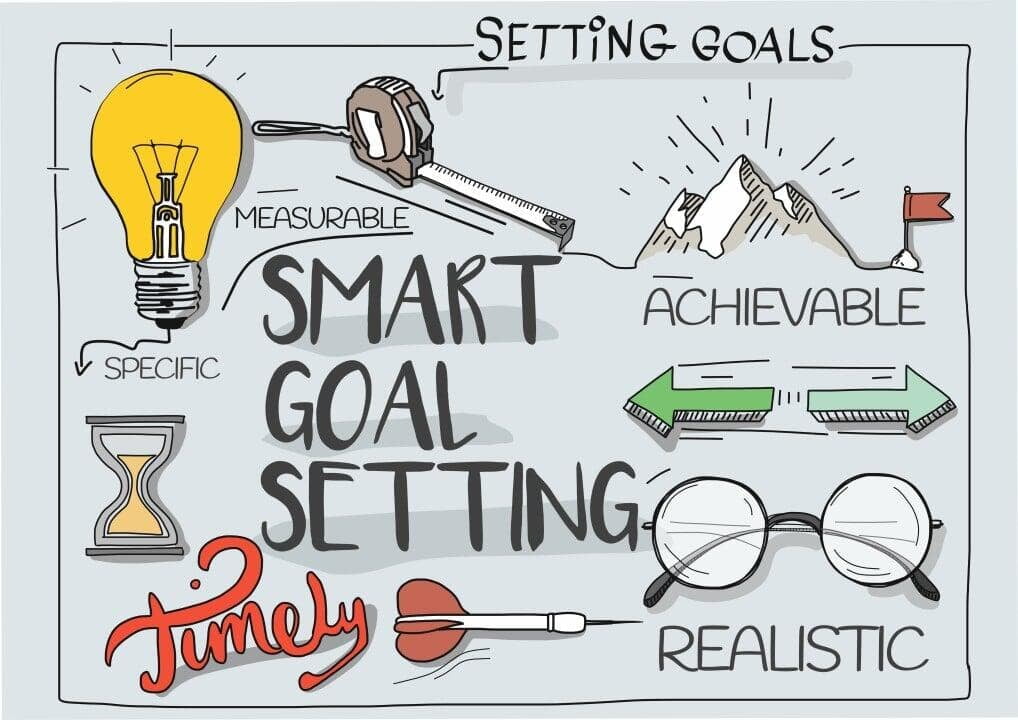

2. Make it SMART.

Goals should be SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-bound to increase their efficacy. (Bovend’Eerdt et al., 2009).

For example, let’s consider my goal: Whenever I begin craving chocolate and/or sweets, I can start eating healthier dessert substitutes, such as chia-seed pudding, oat squares, or dark chocolate date bars.

To make this more SMART, I can consider the following elements:

S: Whenever I begin craving chocolate and/or sweets, I will eat a healthier dessert substitute (i.e., chia-seed pudding, oat squares, or dark chocolate date bars.

M: I will eat one healthier dessert substitute when I experience cravings for chocolate and/or sweets. I will track whenever this occurs, measuring progress or challenges as they occur.

A: I will buy the ingredients to make these healthier dessert substitutes and have them on hand.

R: This goal aligns with my core values of health and promoting my self-confidence.

T: I will start this goal today and continue for the next month.

With the goal you have written on your paper, you can now modify it to incorporate these SMART elements. If you’d like to, you can write the goal out using this framework, including separate elements for each SMART element (i.e., S, M, A, R, & T).

Research has highlighted the power of visualizing future achievements, that is, imagining yourself achieving your goals. An interesting psychology study (Vasquez & Buehler, 2007) found that university students who completed an imagined future success scenario from a third-person perspective (e.g., pretending to be an observer watching themselves), as opposed to a first person perspective (e.g., imagining through their own eyes) reported higher motivation to achieve success. It is worth giving this method a try! Frequently practise visualizing your future success from a third-party omniscient. Importantly, detail is key to tap into the senses.

When imagining your success scenario, you may use the following prompts to guide you:

What’s happening?

Where are you?

Are you sitting down or walking around?

Who is around you? Are you alone?

Is there sound? Who is speaking? Are you chatting with someone?

Are people talking to you? Cheering you? Smiling at you?

How are you feeling?

Now, you should have a pretty decent goal blueprint on your sheet of paper. We have drafted a realistic framework for a goal that will allow us to get from point A to B. Once you successfully achieve this step, you can then work towards a goal that will get you from point B to C, C to D, D to E, and so on. Importantly, reward yourself when you achieve these steps! Take the night off. Watch a movie. Do what you need to feel rewarded. These steps may seem small, but they require a lot of hard work, determination, and rewiring.

I wish you the best of luck in your goal-setting adventures!

“If you want to live a happy life, tie it to a goal, not to people or things.”

Albert Einstein

References

Bailey, R. R. (2017). Goal Setting and Action Planning for Health Behavior Change. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 13(6), 615–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617729634

Berkman, E. T. (2018). The Neuroscience of Goals and Behavior Change. Consulting Psychology Journal, 70(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000094

Bovend’Eerdt, T. J. H., Botell, R. E., & Wade, D. T. (2009). Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: A practical guide. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(4), 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101741

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Gauggel, S., Hoop, M., & Werner, K. (2002). Assigned versus self-set goals and their impact on the performance of brain-damaged patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 24(8), 1070–1080. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.24.8.1070.8377

Vasquez, N., & Buehler, R. (2007). Seeing Future Success: Does Imagery Perspective Influence Achievement Motivation? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(10), 1392–1405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207304541