Enhance your Mindfulness Practice with the Online Becoming Yourself series

Author:Adile Nexha

Graduate life can be stressful in and of itself without adding a global pandemic to the mix. Perhaps reducing the catastrophic ramifications of the pandemic to how it has impacted our graduate studies is reductive, but we are graduate students, and the pandemic has significantly derailed our livelihood in at least one way or another. Many of us were unable to continue our hands-on research in our field of choice and have had to change our focus to online research, or simply put our research on hold while tackling other projects that could be done remotely. While some people can thrive working from home, others like to keep a clear divide between their home and work lives. Regardless, merging work and home environments likely caused a complete shift in daily routines, further contributing to the stress brought on by the pandemic.

It is well known that acute productive anxiety can give us a boost to complete the tasks we have on our to-do lists, like writing that paper or preparing for a committee meeting. However, when faced with chronic, severe, unproductive anxiety that is more difficult to escape (such as that of a pandemic), our brain encounters mental stress that can become counterproductive. Under the stress response, many brain regions, such as the amygdala, are prone to increased activation1 and structural changes due to stress-induced plasticity2.

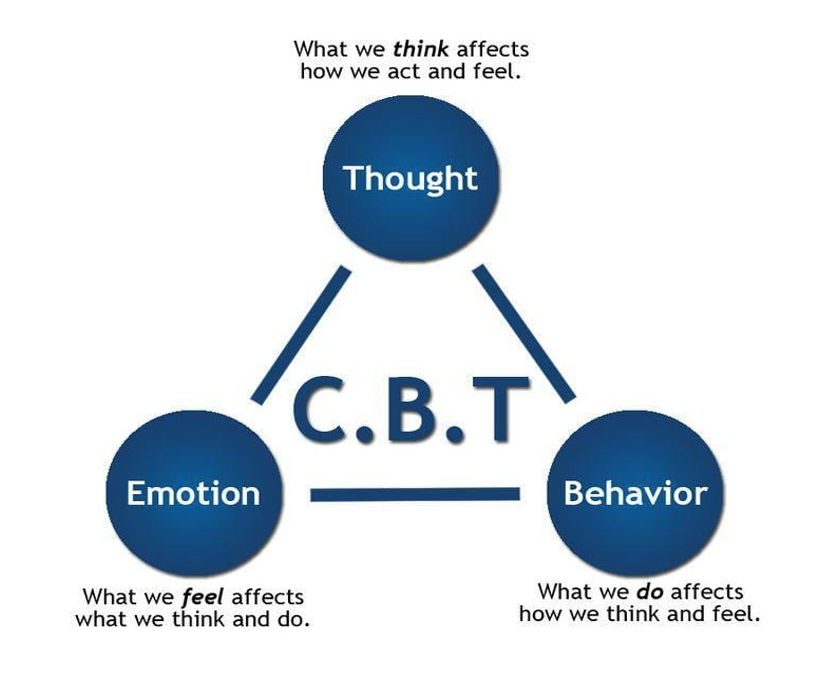

One of the most successful therapies used for individuals with anxiety is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)3, which has been linked to reduced amygdala responsivity mediated by decreased amygdala grey matter volume4. These structural and functional changes in the brain were accompanied by reduced anxiety after treatment, further emphasizing the interconnectedness between brain and behaviour. A subtype of CBT, acceptance-based behaviour therapy, has also led to marked reductions in anxiety symptoms that lasted for months after treatment5. Other treatments, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy focus on mindfulness as a tool to reduce anxiety and stress.

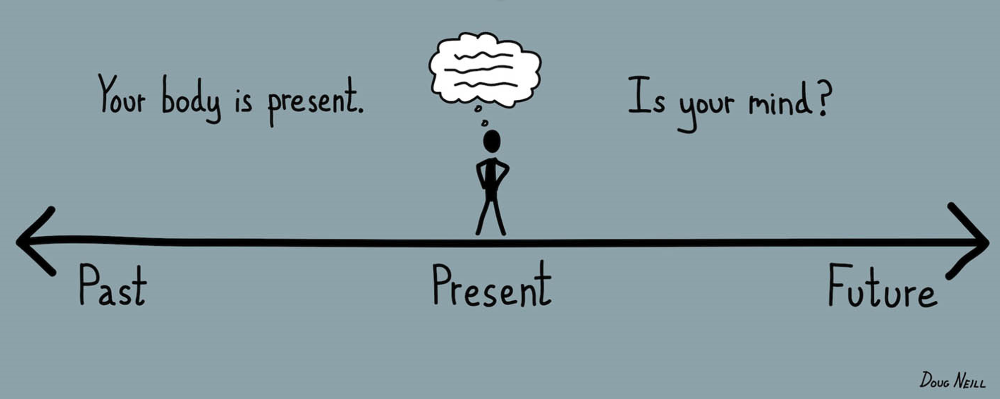

Outside of controlled clinical trials, mindfulness practice has also been used to improve mental health through training the mind to focus on the present and preventing the rumination of thoughts on the past or the future, where anxiety typically lies. Through my own personal experience of practicing mindfulness, I have learned just how restless the mind can be. If there are no stimuli in front of you - such as a computer, TV or phone screen, no music playing, no books or articles - chances are your mind will still be racing. Random thoughts will pop in unprovoked, like wondering what your best friend from third grade is going, if orchids come in different colours, when the leaves started turning yellow, and honestly, what exactly is string theory? In fact, keeping the mind free of rumination and fully focused on the present moment is much more challenging than it sounds. The act of willingly and purposefully dismissing intrusive and distracting thoughts requires practice, just like any other skill.

Unfortunately, the benefits of practicing this skill are not immediately obvious. In an age of endless entertainment at our fingertips, it’s easy to trade in mindful awareness for absolutely anything else – there are a million things you could be doing instead. With a seemingly innate need to seek instant gratification, I tried and failed to be mindful for months. I downloaded meditation apps and I tried creating my own mindful routines, catching only glimpses of the peaceful feeling that came with being fully present. It was not easy to immerse myself in the culture of meditation and mindfulness – I often became aggravated when I couldn’t keep intrusive thoughts away for more than a few seconds.

Through my own self-interest, I joined the Becoming Yourself Series (BYS), a part of McMaster’s Open Circle program, which became the catalyst to improving my mindfulness practice. This program introduced me to the concepts of mindfulness and meditation through daily exercises and weekly logs to track my progress. These little voluntary “assignments” kept me motivated to complete them, sneakily forming a consistent practice of daily mindfulness and meditation. In the program’s weekly meetings, our small group reconvened to share our experiences and explore more mindful techniques with the help of the program’s host, Marybeth. Consistently, she introduced us to new tools to elevate our mindfulness practices and explore the way we experience the world, all in a non-judgemental shared space.

“I developed the BYS program in response to the need I hear among students to pause in the midst of the demands of school and explore one’s authentic self without external pressures,” Marybeth said. “The Becoming Yourself series teaches practices of awareness, self-care, and self-compassion as a key foundation for this process of authentic living.”

When asked what mindfulness means to her, Marybeth said, "Our minds are so often distracted by worries about the future or ruminations on the past. Practicing awareness through meditation, journaling, body-awareness practices, creative expression, or other ways to tune into process in the moment instead of a future outcome helps me to pay attention to my life with openness and curiosity. Through these practices, my trust grows and I sense that I’m held in a larger story."

Taking into consideration the complexities of our individual lives, it is a difficult task to imagine our existence as part of a larger story while focusing on the present moment at the same time. With conscious practice of mindfulness and meditation, I learned that the two concepts are quite intertwined. Through paying attention to the present, a new appreciation of life grows, and those situations of high stress and anxiety are truly put into perspective. And we all know how quickly life as a graduate student can become overwhelming. I hope this article plants a seed in your mind to give mindfulness a try so that you can learn how to manage stress a bit better and experience life more holistically. The Becoming Yourself Series is a great place to start.

You can find more information on the Becoming Yourself Series 6.0: Mindfulness, Balance, and Growth here:

https://opencircle.mcmaster.ca/bys

2. Roozendaal, B., McEwen, B. and Chattarji, S., 2009. Stress, memory and the amygdala. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), pp.423-433.

3. Borza L. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 19(2), 203–208.

4. Månsson, K., Salami, A., Frick, A., Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., Furmark, T. and Boraxbekk, C., 2016. Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Translational Psychiatry, 6(2), pp.e727-e727.

5. Roemer, L., Orsillo, S. M., & Salters-Pedneault, K. (2008). Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 76(6), 1083–1089.