Two-point orientation discrimination versus the traditional two-point test for tactile spatial acuity assessment

SUMMARY: Jonathan Tong

For decades, neurologists have used two-point discrimination (2PD) as a tool for diagnosing neurological dysfunction. 2PD involves stimulating a patient with the tips of a caliper and asking: "were you touched with two points or one?" As the separation between tips decreases to zero, so too should the patient's probability of responding "two-points"; the reasoning for this is that two points that fall between adjacent touch receptors should not be reliably distinguishable from a single point between these same receptors. Remarkably, many patients are able to reliably distinguish two points from one, even when the two points have zero separation (Johnson & Phillips, 1981). This "hyperacuity" might be explained by the fact that a single receptor neuron fires a greater number of impulses to a single indentation than to a double indentation of the same depth (Vega-Bermudez & Johnson, 1999), thus leading to a magnitude difference that the brain can use to discriminate two points at extremely small spacing. We have designed a new clinical screening test that avoids this "magnitude-cue" confound: by having patients identify the orientation of two-point stimuli (horizontal or vertical) in a two-point orientation discrimination (2POD) task, patients must rely on purely spatial information to discern orientation. As expected for a true measure of spatial acuity, 2POD performance approaches chance levels at zero separation, unlike the 2PD task. We recommend replacing the 2PD task with 2POD in clinical settings.

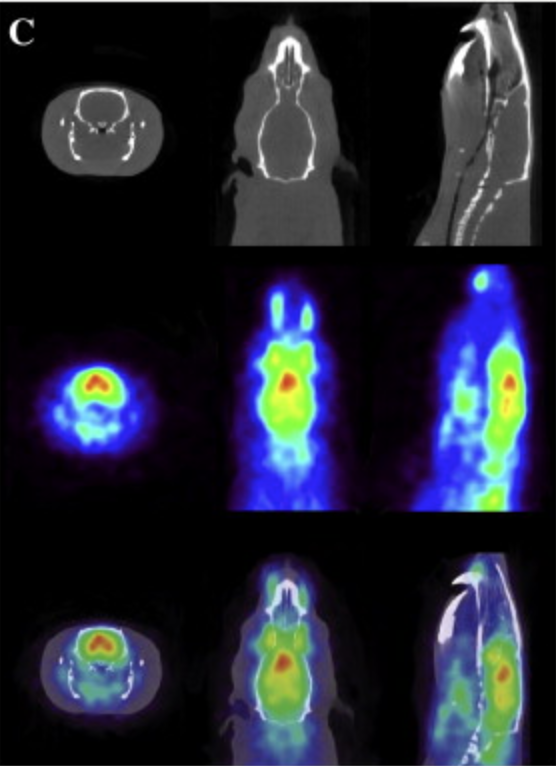

Effects of MK-801 treatment across several pre-clinical analyses including a novel assessment of brain metabolic function utilizing PET and CT fused imaging in live rats.

SUMMARY: Ritesh Daya